Science with Bling: Turning Graphite into Diamond

SLAC researchers have found a new way to transform graphite into diamond. The approach may have implications for industrial applications ranging from cutting tools to electronic devices.

By Manuel Gnida

A research team led by SLAC scientists has uncovered a potential new route to produce thin diamond films for a variety of industrial applications, from cutting tools to electronic devices to electrochemical sensors.

The scientists added a few layers of graphene – one-atom thick sheets of graphite – to a metal support and exposed the topmost layer to hydrogen. To their surprise, the reaction at the surface set off a domino effect that altered the structure of all the graphene layers from graphite-like to diamond-like.

"We provide the first experimental evidence that hydrogenation can induce such a transition in graphene," says Sarp Kaya, researcher at the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis and corresponding author of the recent study.

From Pencil Lead to Diamond

Graphite and diamond are two forms of the same chemical element, carbon. Yet, their properties could not be any more different. In graphite, carbon atoms are arranged in planar sheets that can easily glide against each other. This structure makes the material very soft and it can be used in products such as pencil lead.

In diamond, on the other hand, the carbon atoms are strongly bonded in all directions; thus diamond is extremely hard. Besides mechanical strength, its extraordinary electrical, optical and chemical properties contribute to diamond’s great value for industrial applications.

Scientists want to understand and control the structural transition between different carbon forms in order to selectively transform one into another. One way to turn graphite into diamond is by applying pressure. However, since graphite is the most stable form of carbon under normal conditions, it takes approximately 150,000 times the atmospheric pressure at the Earth's surface to do so.

Now, an alternative way that works on the nanoscale is within grasp. "Our study shows that hydrogenation of graphene could be a new route to synthesize ultrathin diamond-like films without applying pressure," Kaya says.

Domino Effect

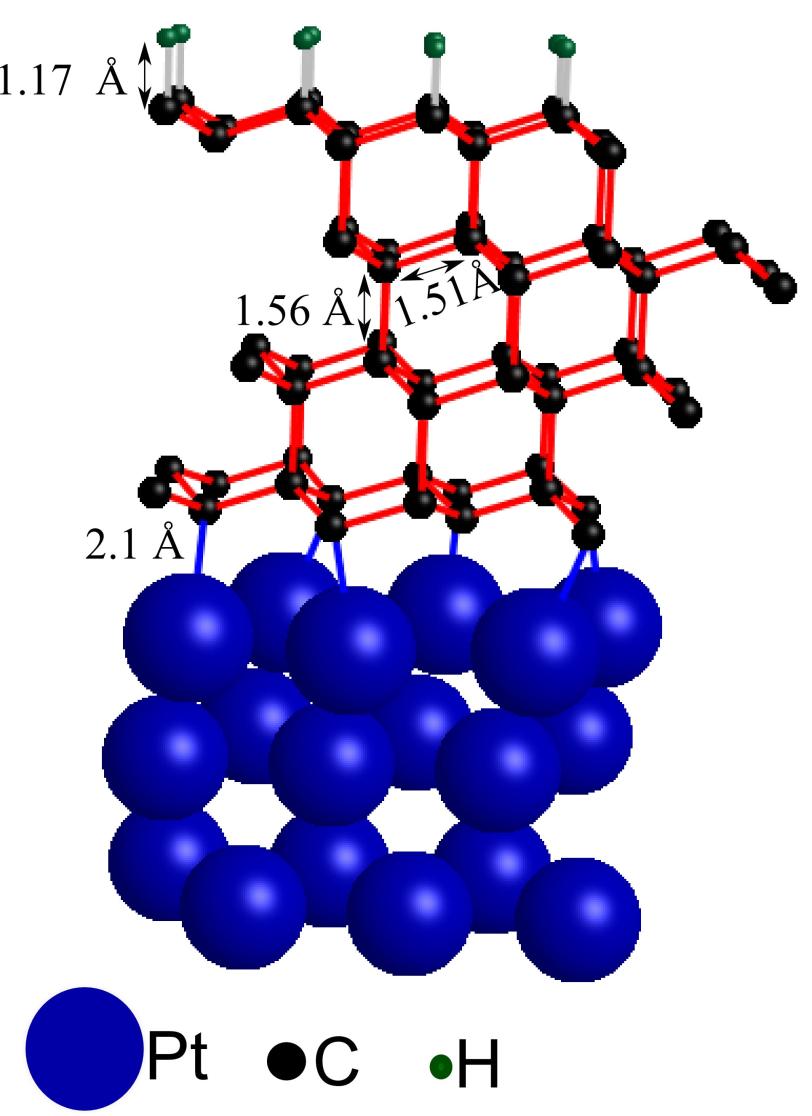

For their experiments, the researchers loaded a platinum support with up to four sheets of graphene and added hydrogen to the topmost layer. With the help of intense X-rays from SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL, Beam Line 13-2) and additional theoretical calculations performed by SUNCAT researcher Frank Abild-Pedersen, the team then determined how hydrogen impacted the layered structure.

They found that hydrogen binding initiated a domino effect, with structural changes propagating from the sample's surface through all the carbon layers underneath, turning the initial graphite-like structure of planar carbon sheets into an arrangement of carbon atoms that resembles diamond.

The discovery was unexpected. The original goal of the experiment was to see if adding hydrogen could alter graphene's properties in a way that would make it useable in transistors, the fundamental building block of electronic devices. Instead, the scientists discovered that hydrogen binding resulted in the formation of chemical bonds between graphene and the platinum substrate.

It turns out that these bonds are crucial for the domino effect. "For this process to be stable, the platinum substrate needs to bond to the carbon layer closest to it," Kaya explains. "Platinum's ability to form these bonds determines the overall stability of the diamond-like film."

Future research will explore the full potential of hydrogenated few-layer graphene for applications in the material sciences. It will be particularly interesting to determine if diamond-like films can be grown on other metal substrates, using graphene of various thicknesses.

The research team included scientists from Stanford University, the Stanford Institute for Materials & Energy Sciences (SIMES), SUNCAT and SSRL.

Citation: Srivats Rajasekaran et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 20 August 2013 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.085503)

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information, visit ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

The SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis is a partnership between SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. SUNCAT explores the atomic-scale design of catalysts for chemical processes related to energy conversion and storage. For more information, please visit suncat.slac.stanford.edu.

The Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. SIMES studies the nature, properties and synthesis of complex and novel materials in the effort to create clean, renewable energy technologies. For more information, please visit simes.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.